This is the 3rd part of a series of posts that present myths and misunderstandings about the tropical Pacific processes that herald themselves during El Niño and La Niña events. In the posts, I’m simply reproducing chapters from my recently published ebook Who Turned on the Heat?

Many of these myths were created by proponents of manmade global warming who have no understanding of the coupled ocean-air processes that result in El Niño and La Niña events. Those persons look at an El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) index and wrongly assume the index represents all of the processes of ENSO—when, in reality, the index simply shows the impact of El Niño and La Niña events on the variable being measured for that index. ENSO indices (like NINO3.4 region sea surface temperature anomalies presented in the post) do not capture in recharge aspects of La Niña events that are evident in the ocean heat content data for the tropical Pacific and they do not capture the impacts of the discharge and redistribution processes of major El Niño events that are plainly visible in the sea surface temperature anomalies of the Atlantic-Indian-West Pacific Oceans(90S-90N, 80W-180).

For almost 4 years, my presentations about the long-term effects of El Niño and La Niña events indicate the global oceans over the past 30+ years have warmed naturally. The long-term impacts of El Niño and La Niña are blatantly obvious. Proponents of anthropogenic global warming apparently have difficulty comprehending that, so they use misinformation to try to contradict what’s plainly visible. Many of the myths they’ve created are failed attempts to neutralize strong El Niño and La Niña events—to redirect the observable causes of the warming over the past 3 decades from natural factors to manmade greenhouse gases.

The following discussion is from Chapter 7.1 Myth – ENSO Has No Trend and Cannot Contribute to Long-Term Warming. It begins with a reference to Section 5 of Who Turned on the Heat? The chapter titles of that section give a general description of the topics discussed. See the table of contents in the book preview here. Most of those discussions have been presented in numerous posts over the past 4 years at my blog and in cross posts at WattsUpWithThat.

******

We’ve discussed and illustrated in Section 5 of this book how ENSO has been responsible for the warming of global sea surface temperatures over the past 30 years. In fact, the intent of this book was to provide the reader with a strong enough background in ENSO to understand why this myth [ENSO Has No Trend and Cannot Contribute to Long-Term Warming] is wrong. Regardless, let’s examine this myth a little closer and see what else we can learn from it.

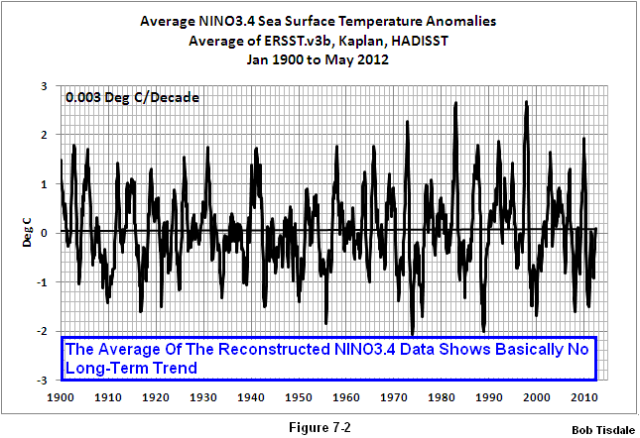

The “ENSO has No Trend” part of this myth depends on the dataset. That is, since 1900, some sea surface temperature-based ENSO indices show long-term trends, warming and cooling; another is flat. Let’s look at NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies using a number of different datasets. We’ll start with ERSST.v3b and Kaplan, both from NOAA, and HADISST from the Hadley Centre. Refer to Figure 7-1. NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies for the ERSST.v3b, Kaplan, and HADISST datasets are available through the KNMI Climate Explorer Monthly Climate Indices webpage. The ERSST.v3b version of NINO3.4 sea surface temperatures has a significant warming trend, while the Kaplan version of NINO3.4 data shows significant cooling. The HADISST-based NINO3.4 data since 1900 has a slightly negative trend, but it’s basically flat.

Figure 7-2 presents the average of the ERSST.v3b, HADISST and Kaplan versions of NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies. The linear trend of 0.003 deg C per decade is basically flat.

HADSST2 and HADSST3 are also available at the Climate Explorer, but their data for the NINO3.4 region are so sparse at times that there are large gaps, with many missing months. Fortunately, a recent climate paper presented an ENSO index based on HADSST2 sea surface temperature anomalies. The paper was Thompson et al (2009) Identifying signatures of natural climate variability in time series of global-mean surface temperature: Methodology and Insights. We’ll discuss this paper again in another myth. Thompson et al (2009) were kind enough to provide data along with their paper. The instructions for use and links to the data are here. Thompson et al (2009) used the sea surface temperature anomalies for Cold Tongue Index region instead of the more commonly used NINO3.4 region. There are very slight differences between the two datasets. Thompson et al also scaled the data so that they could subtract it from global surface temperatures. We’ll standardize it so the dataset doesn’t look so odd, Figure 7-3. The trend clearly shows cooling. That’s even steeper than the cooling trend in the Kaplan NINO3.4 data.

In summary, sea surface temperature anomaly-based ENSO indices do have trends. The trend depends on the dataset. Most show a cooling trend over the 20th century and on into current times.

That’s not the primary fault with that myth. What defies logic with that fairytale is the idea that a variable source of heat with a flat long-term linear trend cannot raise or lower temperatures over periods of time.

For example, let’s say a hospital recently built a new multistory wing. The engineering department has received complaints about the temperature in a storeroom. Rarely does anyone enter the storeroom, but when they do, the temperature there can be very cool or very warm, or sometimes it’s just right. The storeroom is in the center of the building. It’s surrounded by occupied spaces and there are occupied floors above and below it. The temperatures in all of the spaces surrounding the storeroom are controlled by thermostats to maintain temperatures at 21 deg C (70 deg F). The lights in the storeroom are controlled by an occupancy sensor and there is no equipment in that space causing a heat load. Basically, the storeroom has no heat gains or losses when it’s unoccupied. To save on construction costs, hospital administrators elected not to install a thermostat in the storeroom with a separate supply of heating and cooling. The heating and air conditioning system does, however, serve the storeroom, providing a minimum amount of conditioned air for ventilation. The air conditioned or heated supply air comes from a duct that’s controlled by a thermostat in an adjacent office space, which is unfortunately an exterior zone, with heat losses and heat gains and varying occupancy. The head of the engineering department sends a new hire to the storeroom with a couple of temperature sensors and digital recorder.

After a period of time, the new hire stops by the boiler room to consult with the crusty old boiler room foreman. The new hire explains his findings to foreman. The temperature of the storeroom does vary, and he provides a graph that shows the temperature there initially warmed, then cooled slightly, and then warmed again. See Figure 7-4.

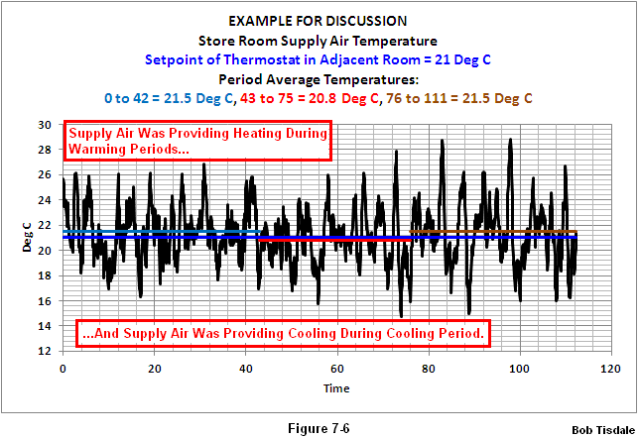

The new hire is baffled, though. The graph of the temperature of the air being supplied to the space, Figure 7-5, shows lots of variability. If he compares the supply air and space temperature, the new hire can see that the temperature of the air being supplied to the space has a strong short-term effect on space temperature. When there’s a short-term supply of warm air, the space temperature warms and, conversely, when there’s a short-term supply of cool air, the space temperature cools. What baffles the new hire is that space temperatures obviously warmed over the long-term, but the supply air temperature shows no trend. In fact, it shows a slight cooling trend.

The boiler room foreman suggests the new hire determine the average temperatures of the supply air entering the space during the early and late warming periods and determine the average supply air temperature for the relatively flat temperature period between them. The new hire returns with a revised graph that shows the average supply air temperatures were in heating mode during the two warming periods and in cooling mode, just slightly, during the period between them. All of the variability had hidden the obvious from him when he looked at the data for the first time. The new hire states the supply air was an uncontrolled supply of variable heating and cooling, and it was causing the space temperatures to warm and cool. The foreman and the new hire go into a more detailed discussion to clarify the reasons for the warming and cooling before the new hire reports back to the head of engineering.

If you hadn’t noticed, I used scaled and ranged NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies since 1900 to create the supply air temperature data in Figures 7.5 and 7.6, and the space temperature in Figure 7-4 bears a striking resemblance to global surface temperatures since 1900 as well. I’m sure some readers will think it was a poor example and that there are better examples I could have used in the discussion above, but let’s look at the bottom line.

Isn’t that all ENSO is? Isn’t ENSO simply a natural, uncontrolled, variable source of heat to the global oceans and atmosphere? Global Land Plus Sea surface temperatures warmed from 1917 to 1944 and warmed again from 1976 to present, and they cooled slightly from 1944 to 1976. Using period-average NINO3.4 sea surface temperatures, we can see that El Niño events dominated the global warming periods, and La Niña events dominated the period between them when global temperatures cooled.

We’ve discussed this in Chapter 5.8 Scientific Studies of the IPCC’s Climate Models Reveal How Poorly the Models Simulate ENSO Processes. Let’s repeat that discussion.

The strength of ENSO phases, along with how often they happen and how long they persist, determine how much heat is released by the tropical Pacific into the atmosphere and how much warm water is transported by ocean currents from the tropics to the poles. During a multidecadal period when El Niño events dominate (a period when El Niño events are stronger, when they occur more often and when they last longer than La Niña events), more heat than normal is released from the tropical Pacific and more warm water than normal is transported by ocean currents toward the poles—with that warm water releasing heat to the atmosphere along the way. As a result, global sea surface and land surface temperatures warm during multidecadal periods when El Niño events dominate. See Figure 7-7. Similarly, global temperatures cool during multidecadal periods when La Niña events are stronger, last longer and occur more often than El Niño events.

The myth “ENSO Has No Trend and Cannot Contribute to Long-Term Warming” is flawed in a number of ways.

THE REST OF THIS SERIES

The remainder of this series of posts will be taken from the following myths and failed arguments. They’re from Section 7 of my book Who Turned on the Heat? I may select them out of the order they’ve been presented here, and I’ll try to remember to include links to the other posts in these lists as the new posts are published.

ALREADY PUBLISHED

1. El Niño-Southern Oscillation Myth 1: El Niño and La Niña Events are Cyclical. Refer also to the cross post at WattsUpWithThat for comments.

2. El Niño-Southern Oscillation Myth 2: A New Myth – ENSO Balances Out to Zero over the Long Term. And please see the WattsUpWithThat cross post.

UPCOMING

Myth – The Effects of La Niña Events on Global Surface Temperatures Oppose those of El Niño Events

Failed Argument – El Niño Events Don’t Create Heat

Myth – El Niño Events Dominated the Recent Warming Period Because of Greenhouse Gases

Myth – ENSO Only Adds Noise to the Instrument Temperature Record and We Can Determine its Effects through Linear Regression Analysis, Then Remove Those Effects, Leaving the Anthropogenic Global Warming Signal

Myth – The Warm Water Available for El Niño Events Can Only be Explained by Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas Forcing

Myth – The Frequency and Strength of El Niño and La Niña Events are Dictated by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation

And I’ll include a few of the failed arguments that have been presented in defense of anthropogenic warming of the global oceans.

Failed Argument – The East Indian-West Pacific and East Pacific Sea Surface Temperature Datasets are Inversely Related. That Is, There’s a Seesaw Effect. One Warms, the Other Cools. They Counteract One Another.

INTERESTED IN LEARNING MORE ABOUT EL NIÑO AND LA NIÑA AND THEIR LONG-TERM EFFECTS ON GLOBAL SEA SURFACE TEMPERATURES?

Why should you be interested? Sea surface temperature records indicate El Niño and La Niña events are responsible for the warming of global sea surface temperature anomalies over the past 30 years, not manmade greenhouse gases. I’ve searched sea surface temperature records for more than 4 years, and I can find no evidence of an anthropogenic greenhouse gas signal. That is, the warming of the global oceans has been caused by Mother Nature, not anthropogenic greenhouse gases.

I’ve recently published my e-book (pdf) about the phenomena called El Niño and La Niña. It’s titled Who Turned on the Heat? with the subtitle The Unsuspected Global Warming Culprit, El Niño Southern Oscillation. It is intended for persons (with or without technical backgrounds) interested in learning about El Niño and La Niña events and in understanding the natural causes of the warming of our global oceans for the past 30 years. Because land surface air temperatures simply exaggerate the natural warming of the global oceans over annual and multidecadal time periods, the vast majority of the warming taking place on land is natural as well. The book is the product of years of research of the satellite-era sea surface temperature data that’s available to the public via the internet. It presents how the data accounts for its warming—and there are no indications the warming was caused by manmade greenhouse gases. None at all.

Who Turned on the Heat?was introduced in the blog post Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about El Niño and La Niña… …Well Just about Everything. The Updated Free Preview includes the Table of Contents; the Introduction; the beginning of Section 1, with the cartoon-like illustrations; the discussion About the Cover; and the Closing. The book was updated recently to correct a few typos.

Please buy a copy. (Credit/Debit Card through PayPal. You do NOT need to open a PayPal account. Simply scroll down past where they ask you to open one.). It’s only US$8.00.

VIDEOS

For those who’d like a more detailed preview of Who Turned on the Heat? see Part 1 and Part 2 of the video series The Natural Warming of the Global Oceans. Part 1 appeared in the 24-hour WattsUpWithThat TV (WUWT-TV) special in November 2012. You may also be interested in the video Dear President Obama: A Video Memo about Climate Change.

Pingback: ENSO Myth Number 4 – The Variations in the East Pacific and the East Indian-West Pacific Sea Surface Temperatures Counteract One Another | Bob Tisdale – Climate Observations

Pingback: ENSO Myth Number 4 – The Variations in the East Pacific and the East Indian-West Pacific Sea Surface Temperatures Counteract One Another | Watts Up With That?

Pingback: ENSO Myth 5 – ENSO Only Adds Noise to the Instrument Temperature Record… | Bob Tisdale – Climate Observations

Pingback: ENSO Myth 5 – ENSO Only Adds Noise to the Instrument Temperature Record… | Watts Up With That?